There are probably as many reasons to read books about books, as there are reasons we read the books themselves.

For me, it's a combination of wanting complementary thoughts about a book I love and the desire to more deeply understand that which I already care about. But what most interests me is not necessarily what interests others who write about books. I look for insights into the craft of story-telling — plot and character, mostly — not so much symbolism and metaphor. In other words: what about a particular novel or story makes me laugh or cry, how is it that one writer's words come alive for me, while another's lie dead on the page?

Samuel R. Delany's classic 1975 novel, the very long, sexually explicit, racially charged, and very strange Dhalgren — a book I discovered when I was 10 or 11 (or maybe 12) and to which I have returned again and again and again (I lost track somewhere after my 20th re-read) — is one of those novels so rich in language, invention, character, and humour (more about which see below) that I have often thought it should have been the subject of numerous dissertations, of long debates in magazines (and later, online), as well as garnering the sort of fan fiction that Star Trek or Star Wars did and does.

It is a novel that sold over a million copies in the first few years after its release as a paperback original, and one that has (mostly) stayed in print ever since; it is one that a lot of writers seem to esteem highly, but it doesn't seem to have garnered the sort of critical attention it deserves.

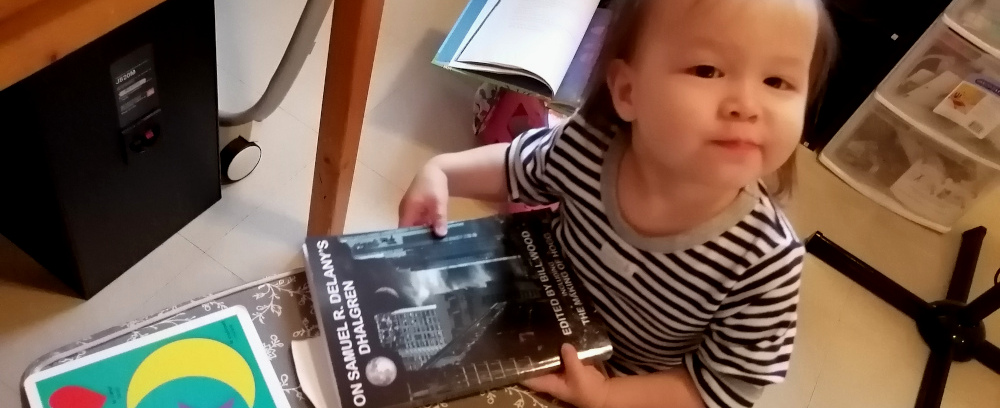

The relatively slender collection of essays and reviews edited by Bill Wood (who doubles as Delany's assistant, among other things), On Samuel R. Delany's Dhalgren, is an attempt to rectify that problem — or at least, to gather together what has been written about that novel.

And, despite the fact that the book is not quite the one I had hoped for, it is a good one, though it left me with the strange feeling that I am not the sort of reader Delany might have expected — would take pleasure in his singular novel. Certainly, if this volume's academic essays are anything to go by, the pleasures I have taken from that novel are not the ones that interest literary critics.

Read more ...