New Morning

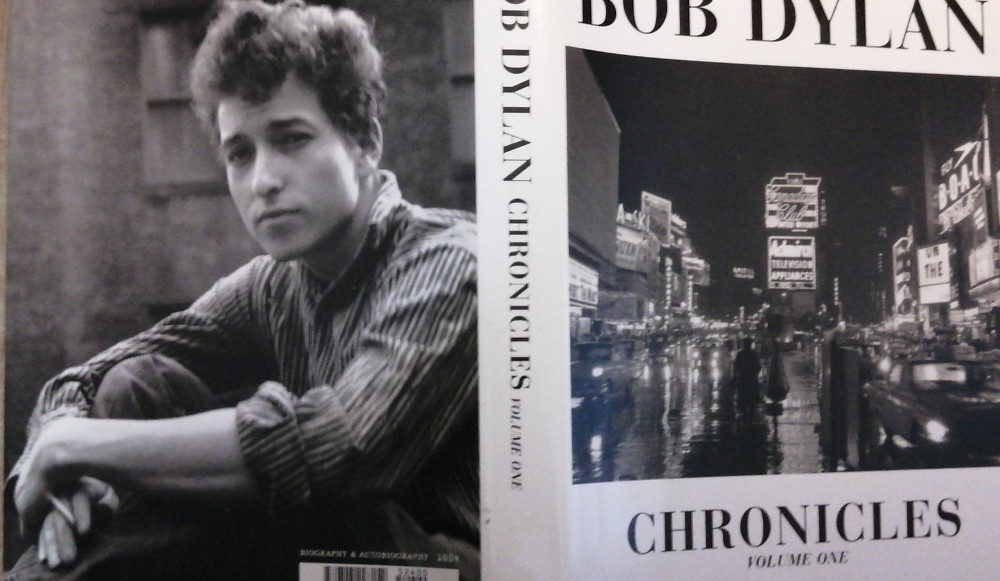

Chronicles, Volume One, by Bob Dylan

The fact that some of my songs were more than twenty years old wouldn't matter. I'd have to start at the bottom and I wasn't even on the bottom yet. There was nothing evolutionary about what I was going to do, no one could have expected it. Without knowing as much, I had a gut feeling that I had created a new genre, a style that didn't exist as of yet and one that would be entirely my own. All the cylinders were working and the vehicle was for hire. I definitely needed a new audience because my audience at that time had more or less grown up on my records and was past the point of accepting me as a new artist and this was understandable. In many ways, this audience was past its prime, its reflexes were shot. They came to stare and not participate. That was okay, but the kind of crowd that would have to find me would be the kind of crowd who didn't know what yesterday was. My fame was immense, could fill a football stadium, but it was like having some weird diploma that won't get you into any college. Promoters didn't want to touch me, either. They'd been burned often in the past and the anger hadn't gone out of them. "I'm all for you," they might say, "but I can't do it." In reality I was just above a club act. Could hardly fill small theaters.

My paternal grandfather died in 1996, at the age of 96. He was born in November of 1899, in Russia under the Czars. When he was born, no man or woman had ever flown; the automobile was a rich man's novelty toy, the telephone and recorded music a rumour from West. He fought in the Russian Revolution and somehow made his way to Canada in 1921.

He always seemed ancient to me. A short, strong, grizzled old man out of a past I could see and sometimes hear, but never touch. He had a round, smooth face and small watery blue eyes that seemed always on the verge of tears. An immigrant of the old school, he worked hard for most of his life, taking a bus to toil in a bakery well into his 80s.

Work and family were what mattered to him. He would take me in a bear hug when I visited — not just me, but all of us — and lay kiss after kiss upon my cheeks.

He was a man of strange contradictions. Cynical about friendship or love, he nevertheless loved his family and seemed to me to enjoy his life, however hard it must have often been.

Through him, my past stretched out long before my birth. Through him, I felt I could almost touch the 19th century. I have long regretted that I didn't have the patience to come through the other side of his lectures and moldy jokes to what my father assures me was a thoughtful and insightful man. Worst of all, for me, was that he spoke with a raspy voice in a thick Russian accent that could have belonged to an immigrant fresh off the boat, not one who had been in Canada for 60 or 70 years.

Nevertheless, through my grandpa, I feel a connection to a not-quite-dead world I have never seen and that I never will.

19th century Russia is not the only time and place to which I feel an affinity beyond the borders of my own life. Science Fiction fandom of the 1930s and 1940s, the Summer of Love and roiling shifts of the 1960s also feel familiar, as if I lived there in another life.

Through books and movies and a few people I've known, I carry the gift of cultures not my own. (That I feel little connection to the popular culture of my own generation is an irony not lost on me; but that is a digression for another time.)

Bob Dylan's Chronicles, Volume One is a powerful addition to the threads in the ever-more complex tapestry of my imagined lives.

Not an autobiography, really, let alone a "chronicle", it can best be described as a meditation, a reflection on one man's life, times and art. Dylan's confident, mostly plain-spoken but sometimes poetic or metaphorical prose is that of a born story-teller. One feels as if in his presence, late at night, perhaps in a quiet speak-easy, sharing a glass while the old man reminisces.

It's probably not the book that most Dylan fans wanted; it is certainly not the book I had expected when I learned that he was writing his memoirs.

If you are looking for kiss and tell or rock 'n roll gossip, or for stories of dissolution and redemption, you'll be disappointed — or, perhaps, happy to have come across something else, something different, something better.

Dylan is not an old man trying to set the record straight nor to settle scores; he is not interested in self-justification nor in self-promotion. Quietly understated, he knows that he has written some good songs, knows that he is a good musician — he doesn't care if we think he has, or is, or not.

Like the Dylan I saw perform a couple of summers ago, Dylan the writer is writing for himself. We are welcome to come along for the ride, but he doesn't really care if we get off before he's finished.

A few years earlier I had read The Prince and had liked it a lot. Most of what Machiavelli said made sense, but certain things stick out wrong — like when he offers the wisdom that it's better to be feared than loved, it kind of makes you wonder if Machiavelli was thinking big. I know what he meant, but sometimes in life, someone who is loved can inspire more fear than Machiavelli ever dreamed of.

Like his best songs, Dylan is in the world, but not quite of it. Again and again, he returns to the folk songs — the music of Woody Guthrie and Robert Johnson, Odetta and many others — and his obsession with that music that set him on the paths he would follow the rest of his life.

A keen observer, Dylan sketches quick portraits of people and places, but especially of his reaction to his musical discoveries and influences.

The book begins and ends at the start of his recording career, jumps back to his early days of passing the hat in coffee-houses and couch-surfing in New York city, then way ahead to a record he made with Daniel Lanois in the late 1980s, a detailed and intense portrait of a frustrating but ultimately successful session in New Orleans. Then he takes us back, to before the beginning, when Minneapolis was his big city, before leading us back to New York and the future that is now long ago in pop culture's past.

Here and there, he answers a few of our questions: the awful records of the early 1970s, in particular, were the response of a man who wanted to destroy the icon he had become.

I had been in a motorcycle accident and I'd been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race. Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on. Outside of my family, nothing held any real interest for me and I was seeing everything through different glasses ...

A few years earlier Ronnie Gilbert, one of The Weavers, had introduced me at one of the Newport Folk Festivals saying, "And here he is . . . take him, you know him, he's yours." I had failed to sense the ominous forebodings in the introduction. Elvis had never even been introduced like that. "Take him, he's yours!" What a crazy thing to say! Screw that. As far as I knew, I didn't belong to anybody then or now. I had a wife and children whom I loved more than anything else in the world. I was trying to provide for them, keep out of trouble, but the big bugs in the press kept promoting me as the mouthpiece, spokesman, or even conscience of a generation. That was funny. All I'd ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities. I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of . . .

He talks about the price of fame — of something more than fame — with a resigned combination of anger, tolerant humour and bemusement. No self-pity, but with a matter-of-fact explanation that, well, it wasn't easy or fun to have crazies marching outside your home, insisting that you come out and lead them ... wherever it was they wanted to go.

Dylan says he didn't want to lead anybody, and I believe him. More than anything else (with the possible exception of his family — but he is so guarded about that it is impossible to be sure; his wives, his children — not one is named), he was an artist. A songwriter and poet, committed to his craft and conscious of the talents and skills he brought to it.

A song is like a dream, and you try to make it come true. They're like strange countries that you have to enter.

Dylan's book is like a song he has made come true, a strange country I am more than happy to have been able to visit.

Add new comment