May 16, 2008 — 1985 saw me dabble in cinephilia. I spent a lot of time at the nearest repertory theatre (at least once, crutched down to Bloor from Saint-Claire and back again; but my Adventures With a Broken Leg are a matter for another day), mostly Hollywood's days of glorious black and white - Casablanca, The Petrified Forest, The Maltese Falcon and other noirish classics, along with features by the Marx Brothers - and who knew that Beat the Devil would turn out to be a comedy! I love Bogart and Bacall, Hepburn and Grant, and of course, Peter Lorre's utterly sleazy supporting roles.

But I did not entirely eschew the current cinema. Two films in particular spoke to me. It was a time, and I was at an age, when the possibility of a nuclear holocaust seemed a clear and present danger; when Ronald Reagan seemed intent on rewriting the word, America, with a 'k' in place of the softer 'c'; when anyone who wanted to know, did know, that "our" side was funding deaths squads in Latin America while undermining democracy at home.

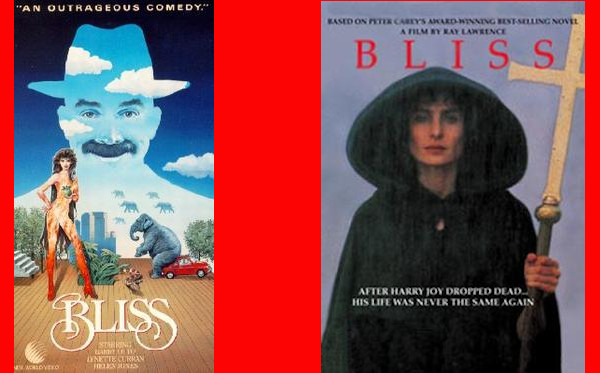

In short, it was a time not entirely unlike today, except (hard as it is to believe) the American President was smarter than the one occupying that House now. And both Terry Gilliam's utterly bleak update of 1984, Brazil and Ray Lawrence's adaptation of the Peter Carey novel, Bliss, a film which matched Gilliam's cynical and despairing vision of our society, while still offering the viewer at least the possibility of redemption and possibly even love.

It was a film that made me laugh, that shocked and appalled me with some of its imagery, and that left me with tears of both joy and sadness with its final, simple, elegiac final voiced over line: "He was our father. He told stories and he planted trees."

I've re-watched the film many times, sometimes alone, sometimes on dates (I even used it as a halfway serious way to vet new or potential girlfriends. The one who looked me in the eye and said, "That's the dumbest movie I've ever seen in my life!", well, we didn't last long. And come to think of it, Laura wasn't much impressed with it either; I should have paid more attention. But I digress), and it still brings tears to my eyes and a catch to my throat.

It's a film that moves me as very few have managed, that speaks to me, in other words.

Some 23 years later, I finally stumbled across a copy of the original, while on a spontaneous visit to my local Sally Ann. As you can imagine, I wanted to love the novel, as well. Since it's a pretty safe rule-of-thumb that the original book is better than the movie, I almost (the movie was too good to trust to rough-and-ready rules, of thumb or otherwise) expected to love it.

I did try Carey's more recent and very well-regarded novel, The True History of the Kelly Gang a few months back, but was unable/unwilling to finish it. The story didn't compel me, the slang (because I wasn't compelled) became a slog and one day I put it down and only picked it up again to shelve it.

I did finish Bliss, and even enjoyed it, but certainly can't bring myself to enthusiastically rave about it.

Bliss is the story of Harry Joy, a successful advertising executive with (he thinks) a wife and children who love him and friends who care about him. The near-death experience with which the novel opens (a heart attack, 9 minutes without a beat; an out-of-body astral projection) establishes both the slightly surreal tone of the book (and imagery in the film) and sets in motion the plot. For when Harry recovers, his illusions have been torn away.

His wife doesn't love him; his son deals drugs; his daughter is a communist who sometimes pays her brother for his drugs with service instead of money. The list goes on.

After a series of "tests" during his recovery, Harry decides that he is in Hell and that his only way out is to be Good.

Naturally, many obstacles and temptations stand in his way (not the least, yet not the most of them, is that his family has him committed to a mental institution whose only interest in him is the income he brings in) and not even the not-at-all stereotypical whore-with-a-heart-of-gold, Honey Barbara, can save him.

Film adaptations of short stories usually work better than adaptations of full-length novels. And maybe that serves to explain what is wrong with Bliss, the novel.

Though the novel clocks in at nearly 300 pages, the film includes nearly all of its scenes. With elegant and meaningful imagery, Ray Lawrence shows where Carey all all too often tells.

The scene in which Harry is told that an elephant sat on his car is, in the film, a very funny minute and a half or so; in the novel, it is several pages of exposition which left me thinking, Yes, I can see how that might be funny, but as Carey wrote it, it barely brought a smile to my lips.

There is enough here to keep you reading, enough to image how Ray Lawrence saw the bones of a very good film hiding among the exposition, but it is not, sadly, a very good book.

Add new comment