Neverwhere: Never Read or Read Again?

Somewhere between 15 and 20 years ago, I read a novel by Neil Gaiman. And not at all long after that, the book disappeared, and I soon realized that I not only had no idea what the title was, but that I had no idea what the book had been about. I had loved his original Sandman comic series (and still do), and so was surprised that I'd found his book, whatever it had been, so decidedly forgetable.

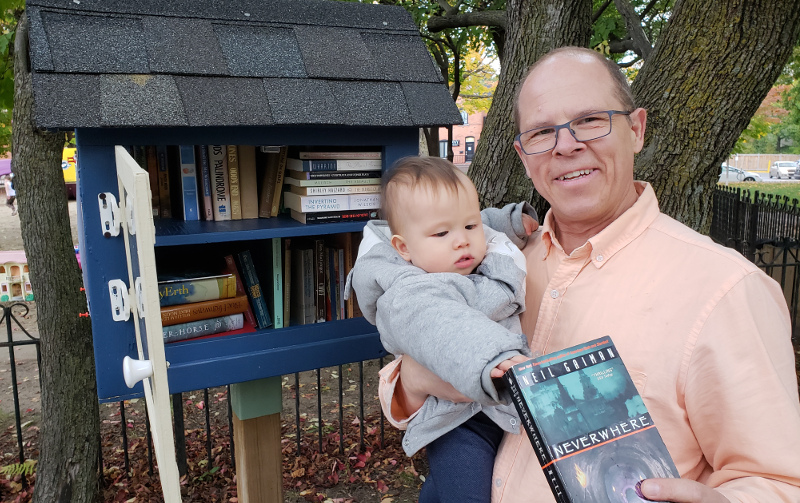

Last week (well, a few weeks ago now that I have managed to find time to finish the review and actually post it), I spotted a well-preserved copy of what I now know was Gaiman's first solo novel, Neverwhere, at a local little library. The cover copy rang no bells, so I decided — Why not? It's free! — to take it home with me.

As I struggled to balance my one year-old daughter in one arm while keeping the paperback out of her reach in the other, a young(ish) woman called out, "Oh, you're going to love that one!" (How is it that almost all the women I see out in public nowadays are "young" or "young(ish)" when I am still so young myself? But I digress.)

Well, then: Did I love it?

No, I did not. If you came to this review via Goodreads, you'll see I gave it three stars, but I struggled a while between two and three before settling on the higher number. The novel is compulsively readable, but it is every bit as forgetable now as it was a decade and a half ago.

The back cover of my copy quotes a review that likens Neverwhere to "A dark contemporary Alice in Wonderland ..." which only serves to prove that that reviewer hadn't read Lewis Carrol's classic diptych in a very long while.

The novel concerns the adventures of one Richard Mayhew, a young businessman who — in the company of his utterly unsympathetic fiancée — stops to help a young woman who is bleeding on the sidewalk. His fiancée warns him that if he doesn't come with her to a dinner meeting with her boss, their marriage will be off; Mayhew does the right thing and brings the young wounded woman home with him.

And soon enough Mayhew and the girl, named "Door" because, we learn later, she is, er, very good at opening locked doors. (Why she gets the special name when the skill runs in the family is never explained.)

The bulk of the novel takes place in "London Below,", a hidden world of tunnels and sewers and abandoned subway stations, of inexplicable magic and of angels locked behind labyrinths beneath the city of London ("London Above"), where the (ahem) underground economy works largely on barter, most of the population seems to consist of members of London's homeless but who have entirely slipped through society's cracks and entered a world of immortal killers mysterious, fog-haunted bridges that are meant to terrify, but don't.

One enters said underworld via invisible doors and, well, it's been a week and a half (now more) since I started this review, and already memory fades.

Suffice it to say that the bulk of the book is a chase. Door's family has been murdered and the murderers are still after her. Richard Mayhew rather unconvincingly develops a relationship, of sorts, with the very young, very manic pixie dream girl, Door, and gradually (but also not too convincingly) makes himself into something of a hero.

I won't offer you more of a synopsis than that; we have Wikipedia for that.

Ludicrous comparisons to Lewis Carrol aside, if Neverwhere reminded me of anything (besides any number of SF/F stories structured as chases) it is the late and much lamented Douglas Adams' Dirk Gently novel, The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul, in which the Dirk finds the old Gods via a secret door (of sorts) in a London train and/or tube station (it's been a while).

Unlike the Adams novel, though, Neverwhere is almost utterly lacking in humour (other than the tediously erudite sadist, Mr. Croup, who speaks in complex sentences full of multi-syllabic words even as he delights in torture and murder; if the characterization of a brutal killer as an smooth-talking aesthete wasn't a cliche in 1996, it certainly is today), nor does it compare in imagination or even plotting.

In Richard Mayhew, Neverwhere gives us a bildungsroman, but Mayhew never really does much of anything. Instead, he stumbles from one near-disaster to another, until — mostly by accident — he manages to fell a monster, the precise nature of which I've already forgotten. As, indeed, I have already once again forgotten the bulk of this book's details.

Three stars? Two stars?

Well, in the moment, Neverwhere is compulsively readable, despite its pedestrian prose and a narrative voice that doesn't sing, but drones, that never changes tone, cadence, or style. No matter who is speaking or what is happening, the story-teller comes across as a reasonably intelligent raconteur at a bar recounting an anecdote at second-hand.

An example, taken at random (by picking up my copy of the book and quoting the first bit of dialogue I came across). In this scene, Richard is being led through London Below by a Rat-Speaker: a "girl" who can communicate with rats. Yes, London Below includes sentient rats, because, well ... why not?

She shut the grille behind her. She was not uncomfortably close to Richard. "Here," she said. She gave him the handle of her little lamp to hold, and she clambered down into the darkness. "There," she said. "That wasn't that bad, was it?" Her face was a few feet below Richard's dangling feet. "Here. Pass me the lamp."

He lowered it down to her. She had to jump to take it from him. "Now," she whispered. "Come on." He edged nervously forward, climbed over the edge, hung for a moment, then let go. He landed on his hands and feet in soft, wet mud. He wiped the mud off his hands onto his sweater. A few feet forward, and Anaesthesia was opening another door. They went through it, and she pulled it closed behind them. "We can talk now," she said. "Not loud. But we can. If you want to."

"Oh. Thanks," said Richard. He couldn't think of anything to say. "So. Um. You're a rat, are you?" he said.

She giggled, like a Japanese girl, covering her face with her hand as she laughed. Then she shook her head, and said, "I should be so lucky. I wish. No, I'm a rat-speaker. We talk to rats."

"What, just chat to them?"

"Oh no. We do stuff for them. I mean," and her tone of voice implied that this was something that might never have occurred to Richard unassisted, "there are some things rats can't do, you know. I mean, not having fingers, and thumbs, an' things. Hang on—" She pressed him against the wall, suddenly, and clamped a filthy hand over his mouth. Then she blew out the candle.

Now, besides the lazy stereotype of the giggling Japanese girl, there's nothing especially wrong with this dialogue (though, had I work-shopped it, I would have suggested fewer "ums"), but as with the novel as a whole, neither is there anything particularly right with it.

The descriptive prose is pedestrian, and the dialogue is generic; besides that single dropped D ("... an' things"), it shows us nothing at all of what the characters are like, nothing of their personalities, let alone their class or individual interests. Why does a sewer-dwelling "girl" who talks with rats sound exactly like Door — another "girl", but one of an established (upper class) London Below family, who sounds pretty much exactly like the bourgeois Richard Mayhew, until very recently of London Above?

In fact, whether from Above or Below, almost all of the novel's major characters sound like generic mid-Atlantic English-speakers, albeit with an inconsistent sprinkling of (I presume) Londonisms. The sole exception is the immortal assassin, Mr. Croup, whose speech is (comedically? I guess it's supposed to be through contrast with his brutality) almost impossibly eloquent. Indeed, Mr. Croup is the novel's only memorable persona, if he doesn't quite achieve a three-dimensional level of realism.

As for the story itself, it consists largely of a chase, as Richard Mayhew stumbles from one fantastical threat to another. As a protagonist, Richard is bland, a pale cut-out going through his paces. Perhaps Gaiman's comic book origins are showing; a decent artist might have provided the reader with the illusion of a three-dimensional character.

Indeed, Gaiman's creations might well have worked nicely in The Sandman, but certainly a quarter of a century after it was written, even the remorseless killers, Mr. Croup and Mr. Vandemar, seem all too familiar.

As for the rest, well, only a few weeks in, I've forgotten all but the broadest strokes of the story; and I think those remain in mind simply because I was determined to review the book even before I opened the cover. Now that I'm at the penultimate paragraph, I feel certain the rest will fade away like the plot of a B-movie not directed by Roger Corman.

In the end, Neverwhere is a novel notable only for being forgettable. It entertains for the duration, then slowly slips, like a dull dream, from memory. Neverwhere is neither a good novel nor a bad one; competently told, it is lacking in originality, passion, or insight. I want to give it two stars out of five, but competence must count for something, so ... three.

And back to the little library it goes ...

Add new comment